Chapter 7: The End of an Era

Infocom Inc., which pioneered the personal computer software text-adventure genre with such fantasy games as Zork, Wishbringer and Leather Goddesses of Phobos, is closing its doors in Cambridge and moving to Menlo Park, Calif., next month.

That's headquarters for Mediagenic, formerly Activision Inc., which purchased Infocom three years ago for close to $9 million. The relocation is a cost-saving measure, since Infocom has been losing an average of $200,000 per fiscal quarter for the past two years, according to Laura L. Stagnitto, Mediagenic's director of corporate communications.

[…]

Another factor for Infocom's declining fortunes is the aging of Infocom's traditional audience, composed of early computer users who spent evenings and weekends hunched over a terminal drawing maps in text-only games that took 20 to 50 hours to solve.

"Computers are a mass-merchandising market and we found it difficult to interest consumers in products that did not capture their attention immediately through superficial characteristics, such as fancy graphics," said Joel Berez, Infocom's founder and former president. Berez resigned last summer to return to his family's 70-year-old housewares business in Pittsburgh.

Mediagenic said it will continue to publish some of Infocom's titles, notably the Zork series, which has sold more than 1 million copies, along with newer software that uses computer graphics.

"It's been sad for me," acknowledged Berez.

-- Ronald Rosenberg (Boston Globe, May 22, 1989)

Over the last few years of the eighties, IF gradually disappeared altogether from the marketplace, as the companies that had published it either shut their doors or found more lucrative areas in which to focus their attentions. By 1990, adventure gaming meant mouse driven, graphical games such as those published by Sierra and Lucasarts, and textual IF was seen, as it still too often is today, as an anachronistic throwback to the early days of the home computer revolution, good for little other than nostalgia.

While it is temping for a self-avowed IF evangelist like myself to rely on arguments such as those of Joel Berez in the Boston Globe article above, stating in effect that gamers were too simple-minded and fixated on superficial flash to appreciate the charms of IF, they represent only a partial truth at best. IF developers did themselves few favors with would-be converts in the eighties. The average specimen from the early part of that era is virtually unplayable in its awfulness, and even efforts from the latter half of the decade, when the inertia of the market had weeded out everyone not seriously dedicated to the genre, pay far too little attention to tenets of game design now taken as accepted wisdom by the modern IF community. While there were diamonds to be found even among games not bearing the Infocom label, they were the exception rather than the rule. Expecting consumers to pay thirty dollars or more for the privilege of being stymied at every turn by willfully unfriendly designs filled with well-nigh insolvable puzzles is not a viable strategy for long-term success. Early on, consumers put up with this sort of thing because there was nothing less frustrating out there. When that changed, though, only the die-hards were left, and when these also fled, so did the commercial era of IF, even though developers had barely scratched the surface of the genre’s potential.

If one is so inclined, one can take a certain solace in the fact that, having killed off commercial IF, graphical adventure gaming would suffer its own decline in commercial fortune over the following decade, and that many of its wounds would be similarly self-inflicted. Today it is thought of by most mainstream gamers in the light that IF was in 1990. That, however, is a story for another essay.

The Decline and Fall of Infocom

While Infocom was largely innocent of the game design sins of its competitors, it ultimately shared their fate. The reasons for Infocom’s failure are complex, and only partially bound up with the market failure of the IF genre as a whole. As it did in so many more positive areas, Infocom blazed its own trail here, sowing the seeds of its destruction even during its glory years when it could seemingly do no wrong.

Studious readers may recall that Infocom was not founded with the intention of being solely a producer of computer games. Many members of the company’s board and most of its principal investors saw games only as a way of bringing in some quick income which could be funneled toward what they saw as the company’s ultimate goal, the production of professional business software. Their attitudes did not change appreciably even after Zork and its immediate successors made of Infocom minor media sensations and one of the most successful computer game publishers in the world. The most vocal proponent of an entry into business software was Board of Directors member Al Vezza. Vezza was older than most of the Infocom staff, having been a professor rather than a student at MIT at the time of the company’s founding. His professional experience and knowledge of the ways of business, not to mention the effect his vote of confidence in this group of scruffy kids had on potential investors and creditors, had been instrumental in getting Infocom off the ground, and everyone tended to defer to him. At Vezza’s prodding, Infocom founded a Business Products Division in the 1982, even in the midst of its first rush of entertainment software success, to develop a new relational database system to be called Cornerstone.

Vezza and Infocom believed that some of the technologies that had come into the company from MIT could be adapted to the world of business, as well as entertainment, software. Most important of these was its Z-Machine virtual machine. In a personal computing world still fragmented into many competing and incompatible operating systems, the Z-Machine could allow Infocom to simultaneously market Cornerstone on many machines, which could then freely exchange data among one another.

During 1983 and 1984, Infocom’s IF business grew at a prodigious rate, but virtually all of the profits thereby, plus considerable funding from outside venture capitalists, were sunk directly into the Business Products Division. By now, Infocom effectively consisted of two different companies with completely different cultures. The Games Division was populated by the irreverent dreamers that were chronicled by many a fascinated reporter of the day; while the the marketeers of the Business Products Division were straight-laced and businesslike. Employees of the Games Division often showed up at noon in sneakers and tee-shirts to work late into the night; while those in the Business Products Division arrived promptly at nine o’clock in pin-striped suits, and left equally promptly at five. Employees of the Games Division dreamed of the potential of IF as a whole new literary form; while those of the Business Products Division dreamed of market penetration and consulting fees. Not surprisingly, there was little love lost between the two halves of the company. The hacker culture of the Games Division frustrated Vezza as he attempted to round up serious business investors:

Vezza also believed that the relaxed, fun-loving engineering culture also worked against the company. He believed that East Coast venture capitalists wanted to invest in serious, professional-looking companies. Investors would initially be impressed with Infocom’s bottom line and potential for growth, but they would be displeased by a lack of a serious atmosphere after they visited Infocom. One firm reportedly told Vezza, “You have a bunch of talented, undisciplined people, and you’re not going to be able to control them” (Briceno 33).

For their part, employees of the Games Division were understandably frustrated at seeing the fruits of all their labors sunk directly into the black hole that was a Business Products Division which had no appreciation whatsoever for what Games was creating. Much of their resentment was directed toward Vezza himself, who was apparently not the most personable of men. Even in 1999, implementer Mike Berlyn was still referring to Vezza as a “weasel-alien” (Berlyn). Vezza was unfazed, however, and continued to consolidate his position as the company’s leading strategist, replacing Games Division loyalist Joel Berez as CEO in January of 1984, although Berez continued to serve as the company's President. By this time, Business Products employed several times the number of people of the Games Division that was the company’s sole source of revenue, and was spending that revenue with reckless abandon on their marketing schemes. Steve Meretzky recalls that a "Don't Panic!" button included with Cornerstone cost fifty cents to manufacture, while a virtually identical one included with the Hitchhiker's game was procured by the Games Division for about ten cents.

Amidst these conflicts, development of Cornerstone ground on, and it was finally released with high expectations and considerable fanfare in January of 1985. These were quickly dashed, as Cornerstone, in spite of possessing a number of clever features and innovations, turned into a complete flop for several very good reasons. For one, while the home computer market would remain rather wild and chaotic for a few more years, the business market had largely settled as its standard computing platform on IBM PC-compatible machines running MS-DOS. This meant that Infocom’s virtual machine technology conveyed no real advantage anymore, and in fact caused Cornerstoneto run sluggishly compared to other databases written as native PC applications. As Vezza had always feared, Infocom’s reputation as a games developer also worked against it here. There is an old adage in corporate America that “no one ever got fired for buying Microsoft,” and, indeed, serious businesses were much more comfortable investing in software from equally serious business software developers such as Microsoft than in Infocom’s product. Cornerstone’s $495 price tag, meanwhile, kept it out of the reach of the individuals and small business owners who might otherwise have been willing to give this unproven company a chance. Once Cornerstone’s complete market failure was obvious, Infocom laid off the entire Business Products Division and instituted a series of stringent cost-cutting measures, even reducing Cornerstone’s price to $99 in a desperate attempt to wring some sort of revenue from the white elephant. Al Vezza stepped down as CEO, to be replaced by the man he had replaced two years before, Joel Berez. It was too little too late, though, as the financial damage to the company was done, even as its games continued to do fairly well. (The December 1985 Softsel chart, for instance, shows a very respectable three Infocom titles amongst the top twenty.)

Saddled with debt from the Cornerstone fiasco, Infocom was left with a stark choice: sell itself to an outside buyer, or go under entirely. Said buyer came along in the nick of time in the form of major computer and console games publisher Activision. The sale was officially agreed to in February of 1986, and completed that June. For Infocom’s remaining employees, it felt like nothing short of a new lease on life. Activision was being run at the time by Jim Levy, a rare computer game executive who actually cared deeply about the artistic potential of interactive narrative, as was evidenced by products like the innovative “computer novel” Portal that he had shepherded to fruition. Naturally, Levy admired Infocom greatly, and jumped at the chance to acquire the company for reasons that seemed to have at least as much to do with his artistic heart as his business head. Levy quickly charmed the initially guarded implementers:

Infocom held a surprise “InfoWedding” with Levy and Berez to commemorate the merger. Levy happily played along as “Rabbi” Galley pronounced Activision and Infocom, “Corporate and Subsidiary.” “The way Levy handled [the wedding] was better than any speech he could have given,” said Meretzky (Briceno 41).

Levy fit right in with Infocom’s irreverent culture. The Summer 1986 addition of The Status Line includes a profile of him in which he lists “collecting companies” as his hobby, names Cornerstone as his favorite Infocom “game,” and gives a one word answer when asked exactly why he chooses to do what he does: alimony. His operating instructions to Infocom were essentially to keep doing what it had been doing, only more so. He encouraged the company to double its rate of game production, from three to five new titles per year to eight to ten. With a slate of new and innovative IF games being given the green light by a supportive parent company and Cornerstone and business products in general a distant memory, Infocom’s future seemed brighter than ever for many of its employees.

Alas, it was to be a false dawn. Perhaps due partly to the financially questionable Infocom acquisition, Levy was replaced as Activision CEO by Bruce Davis at the end of 1986. Davis had been against the Infocom deal from the start. The games that had been approved during Levy’s brief reign would be completed and released throughout 1987, but they would represent not a new beginning but rather Infocom’s last great creative flowering, as Davis pushed the company hard to abandon what he saw as its anachronistic all-text work and move into more lucrative areas. Notes taken by David Lebling at a company meeting conducted on April 29, 1987, have surfaced, and illustrate the confusion and uncertainty that was once again swirling around the company at this time:

There was a great deal of discussion about defining what it is we do. For example, do we just do I.F.? Do we do anything that has an English parser in it? Do we have to have puzzles? Do we have to have stories? If you do a point-and-click interface (like Deja Vu) is it still "what we do"?

Frustration is also expressed at a gaming press that continually dismisses Infocom’s products as outdated:

Some people in the market seem to believe that I.F. technology, particularly ours, hasn't advanced in years. They don't notice the small improvements in the parser and substrate, probably because to a casual observer, our newest games look a lot like our first ones.

[Apparently, Personal Computing is doing a piece on new stuff, and said they weren't including anything of ours (when asked) because it's "old hat."]

Ultimately, the powers that were at Activision would allow Infocom only one way forward. Once the pipeline was cleared of all-text works currently in production, Infocom’s future games would have to include graphics. The implementers set about responding to this technical challenge the way they always had, by creating a new version of the venerable Z-Machine. Version 6 doubled the maximum allowable story size yet again, to 512K, although no released game would come anywhere close to using all that capacity. More noticeably, version 6 allowed the display of illustrations, along with elaborate borders and attractive colors.

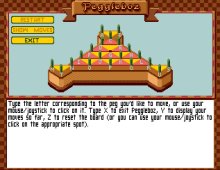

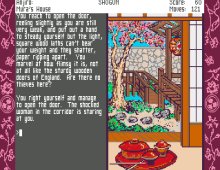

Screens from Infocom’s late illustrated games Zork Zero and Shogun

There is certainly nothing inherently wrong with the concept of illustrated IF, but the four games produced in this format, which together represent Infocom’s swan song, are a rather uninspiring lot when compared with what had come before. The first to appear was Steve Meretzky’s Zork Zero, yet another trip to the well of the Zork universe that Activision must have thought of as the closest thing Infocom had to a sure bet at this point. There are some clever puzzles, and the game is suffused with Meretzky’s trademark gonzo humor, but the whole feels rather workmanlike and tired, especially when compared to the bold experimentation of the previous year’s all-text work.

Zork Zero was, however, a masterpiece in comparison with Shogun, Infocom’s adaptation of James Clavell’s best-selling novel and equally successful television mini-series. The project was apparently foisted upon Infocom by Activision executives who saw the property as a sure thing. (Adaptations from other media were in fact a major cornerstone of Activision’s business plans in all gaming genres at the time.) The original plan had called for Clavell to actively collaborate with David Lebling on the game in a similar manner to Douglas Adams' involvement with the Hitchhiker game, but that never materialized. Clavell in 1988 was aging and in poor health, and struggling to complete what would turn out to be his final novel. He had little time, energy, or interest to give Infocom’s project. Lebling:

What I ended up writing is a sort of "Scenes From..." game. It has some good parts, I think (a couple of timing puzzles that are very intricate), and Donald Langosy did a superb job on the graphic add-ins. However, as a whole I have to consider it a failure. The technology wasn't (and still isn't) ready for a plot-and-character-heavy adventure game (Granade).

Most of the game’s text is lifted verbatim from the novel, and many parts are barely interactive at all. Most of its “puzzles” consist of simply doing exactly what John Blackthorne did in the book, however arbitrary or random those actions may seem in the context of the game. Those who attempt the game without having read the book obviously have a problem on this front. Lebling considers Shogun to be by far is most disappointing work for Infocom, and few would argue with him on this point. Its only redeeming qualities are its lovely Japanese-style illustrations and the endlessly amusing fact that it is the only Infocom game in which the player is required to “make love to” another character to advance the plot. The reason is of course that this is what Blackthorne did in the book.

Of the remaining two graphical efforts, Journey is a rather generic, albeit well-written, fantasy adventure from Marc Blank that abandons the parser entirely in favor of a menu-driven interface, thus turning it into a sort of elaborate computerized Choose Your Own Adventure book. Infocom’s final released game, Arthur: The Quest for Excaliber, was not produced in-house at all, but was rather written by a Virginia-based outside contractor named Bob Bates using the company’s tools. While hardly innovative in either its Arthurian subject matter or its standard text adventure construction, it is well-crafted and entertaining. Certainly companies have gone out on worse notes.

Even as these titles were in production, the writing was on the wall, and Infocom’s number of employees steadily dwindled. Brian Moriarty jumped ship to Lucasarts, where he would design the acclaimed graphical adventure Loom, and Joel Berez, President of a company that was literally eroding away below him, resigned to join his family’s business in Pittsburgh. None of the first three illustrated adventures sold particularly well, and the axe finally fell before Arthur had even hit the shelves. A series of substandard games had left Activision suffering serious financial woes of its own which prompted it to briefly rename itself to Mediagenic in the hope of a fresh start of sorts. Its situation being what it was, Mediagenic had little patience with a money-losing subsidiary involved in the niche genre of IF, and shut the doors of Infocom’s Cambridge offices in May of 1989. Eleven of Infocom’s twenty-six remaining employees were offered the opportunity to move to California and continue on with Mediagenic, but only five accepted. Infocom was no more, having died with a whimper rather than a bang.

It is tempting to speculate at this point on what Infocom might have achieved had it not made the fateful decision to mortgage its future on Cornerstone. Certainly the company might have lasted longer, or perhaps even still be with us today, if it had concentrated on its core strength of developing games. Still, whether Infocom could have continued to release IF games for an appreciably longer time is by no means certain. By 1990, there were exactly two commercial IF publishers left in the world, and four years after that there were none. It is highly doubtful that Infocom could have found a way around the market pressures that led to this. I suspect that Infocom would have been forced out of IF development even if it had survived. Whatever took IF’s place with the company would quite possibly have been interesting and worthwhile in its own right, for the implementers were a prodigiously talented and creative lot, but I seriously doubt that even a well-managed alternate Infocom would still be releasing IF today. Al Vezza has much to answer for with regard to his misguided plans, but we cannot lay the death of commercial IF at his feet.

Mediagenic would soon reclaim its heritage by changing its name back to Activision, and the Infocom name, if not the company, also would live on for a while. Indeed, Activision had begun the practice of branding games that did not originate from the company’s Cambridge offices with the Infocom label as early as 1987. Most notable of these was the almost comically awful InfoComics line of “interactive comic books,” based on characters and settings from Infocom’s previous IF works but developed by Tom Snyder Productions. Infocom loathed these titles, but dutifully bits its lip and promoted them in The Status Line. After 1989, Activision continued to occasionally slap the Infocom name on its graphical adventures, and made use of some of the company’s intellectual property as well. Three graphical CD-ROM Zork adventures were produced – Return to Zork, Zork: Nemesis, and Zork: Grand Inquisitor – which are, respectively, thoroughly underwhelming, decent if a bit dull, and surprisingly good. A graphical sequel to Leather Goddesses of Phobos also appeared which has attained a sort of retrograde notoriety as a game that is so bad it is almost good, and a third Planetfall game spent considerable time in production, only to be cancelled. Activision also made a habit for years of periodically re-packaging and re-releasing the old Infocom IF games in various compilations and value-packs, most of which did surprisingly well. It has been almost a decade, however, since Activision has made any use of the Infocom name or intellectual property.

After Infocom’s final dismantling, many of the implementers decided they had had enough of the fickle computer game industry. David Lebling and Stu Galley entered the world of business data processing, where the work may not be as exciting but the hours are shorter and the pay is better. Amy Briggs returned to university to become a cognitive psychologist. Marc Blank and Mike Berlyn remained in the industry, but to work on non-IF games. Two of the implementers, however, were not quite willing to give up on IF. Out of their stubbornness was born Legend Entertainment, the last commercial IF producer of the era.

Legend Entertainment

Implementer Bob Bates had an odd relationship with Infocom. He was never a true employee of the company, but rather the head of his own Virginia firm, Challenge Entertainment, who contracted with Infocom in 1986 to develop games with its technology. The resulting titles, Sherlock: Riddle of the Crown Jewels and Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur, were then released by Infocom just as all of its other in-house written games. Both titles were solidly put together under the late Infocom philosophy of proper game design, but neither was particularly notable for its innovation. Indeed, if Bates had done no other work in IF, his biggest claim to fame would be a melancholy one, for he authored both the last all-text Infocom game (Sherlock) and its final game period (Arthur).

Bates was apparently of an entrepreneurial bent, for upon Infocom’s demise he decided to reorganize Challenge into a full-fledged publisher to continue Infocom’s legacy, as it were. On the face of it, this was dicey proposition indeed. By 1990, the only IF publisher of the eighties that still remained in that business was Magnetic Scrolls, and commercial IF increasingly seemed a thing of the past. Bates believed, however, that there was still life in the genre, as long as the player was offered more than just text. Bates and his company, Legend Entertainment, would effectively take the path Infocom had begun to explore with its late multimedia experiments to its natural conclusion, wrapping not only colorful graphics but also full music scores, sound effects, and even the occasional animated “cut scene” around the basic IF model of typing and reading. Legend would follow the trail blazed by Magnetic Scrolls in Wonderland in making even the typing optional by providing the user with context sensitive menus of verbs, prepositions, and nouns from which she could, if she chose, build sentences without doing any typing at all. Also included were other convenient features, such as an auto-map, designed to take much of the manual labor out of playing IF. All of these bells and whistles would come at a cost, however. The technical hurdles that had to be cleared to implement of this would force Legend to abandon the Infocom tradition of supporting many computers and operating systems. It would instead target its work strictly toward the IBM PC compatibles that were by now coming to slowly strangle their competitors and dominate the home computer market. Bates did however carry over to Legend one much more tangible legacy of his time with Infocom: he was able to convince Steve Meretzky, creator of some of Infocom’s most popular titles, to write IF for the new company. Apparently Bates’ ambitious new interface design and Meretzky’s involvement were enough to convince prospective investors that commercial IF still had life. With their help, Legend Entertainment was officially formed bare weeks after Infocom’s final closing, and Bates and Meretzky each began to work immediately on a first game for the new company.

Screens from Legend’s Timequest

Meretzky’s creation was a comedy called Spellcasting 101: Sorcerers Get All the Girls. The player takes the role of Ernie Eaglebeak, a nerdy freshman just entering Sorcerer U., a sort of university of magic and, of course, a reference to Meretzky’s Infocom game of the same name. In Spellcasting, Ernie must pass his exams and, more importantly, seduce several of the more attractive females on campus. The game allows Meretzky to indulge in the same sort of risqué humor we previously saw in Leather Goddesses of Phobos, while also poking plenty of broad fun at college life. Fraternities at Sorcerer U., for instance, are named Tappa Kegga Bru and I Phelta Thi. The game as a whole is well-designed, and the humor hits often enough to give it a certain charm, but it does feel a bit disappointing to see Meretzky merely treading water with the same fraternity brother humor he had perfected years before. That disappointment only increases when looking at the two sequels the game spawned. Together, these three games make up Meretzky’s entire IF output for Legend. Even as one can appreciate them for the amusing trifles they are, one cannot help but wish that Meretzky had seen fit to challenge himself and his audience a bit more.

Bob Bates’ first Legend game, a time travel adventure appropriately entitled Timequest, was both much more ambitious and much more satisfying. Its plot – not its strongest suit -- involves one Zeke Vettenmyer, who (in addition to being an anagram for Steve Meretzky) is a rogue member of the Temporal Corps, a sort of cross-time police force to which the player also belongs. Vettenmyer has subtly altered ten pivotal historical events in a plan to bring about the destruction of the world. The player, naturally, much chase this madman through time undoing the damage he causes and restoring the timestream to its proper order. By far the best aspect of the game is its historically accurate depictions of many locations and time periods, which range from 1361 BC to 1940 AD. To undo Vettenmyer’s ten changes, the player will need to visit some thirty-five separate timeplaces, exploring, solving puzzles, and collecting items that will often be needed in other timeplaces. The game is non-linear and bewilderingly complex, yet there is real fascination in putting all of the pieces together. It is undeniably difficult, yet the game leaves the player wanting to solve its mysteries unaided. One of the central tenets behind Timequest, and Bates’ other IF work, is the concept of “player empathy.” Bates:

To determine what is "fair and reasonable" you need to be able to put yourself in the player’s shoes. You need to develop what I call "player empathy." This is the ability to look at the game from the player’s point of view, even though the game is still nothing more than a swirling design in your head. You must, as the potential player, be able to say, "This is the situation I’m in, and here is what I’ve been told. I know my long term goal, and I know my short term goal within this scene, but right now I’m being blocked by these two problems. Now… how am I going to solve them?"

Once you can look at the game from the player’s point of view, you can anticipate the kinds of things he is going to want to try. And once you have learned to anticipate his moves, you can give him a better game experience by writing non-default reactions to them (Bates).

Bates has spoken and written quite extensively on the nebulous concept of “fairness” in adventure gaming:

In a fair game, the answer to every puzzle is contained within the game. In addition, a player should theoretically be able to solve it the first time he encounters it simply by thinking hard enough (assuming he has been presented with all the information). Like a good mystery novel, it isn’t fair to wait until the last page, only to have the author reveal previously-withheld information that identifies the murderer (Bates).

The fact that Timequest consistently plays fair makes its complexities fascinating rather than frustrating. The player can put her faith in the game, without worrying whether the puzzle that currently has her stumped has some arbitrary solution she will never stumble over except through blind trial and error. This feeling is unfortunately all too rare in IF of the commercial era.

Some of the pivotal historical events are the sorts of things one might expect. Others initially seem like trivialities, yet show a real awareness of how the tides of history can turn on such seemingly inconsequential events. Legend’s multimedia enhancements work wonders here. The pictures and especially the temporally and culturally correct music for each event combine to set the mood wonderfully. In addition to its fun quotient, Timequest has real educational value. On the whole, it is not only Legend’s largest and most ambitious IF title, but also its most satisfying, and indeed one of the best all-around games of the commercial IF era. It stands today with Graham Nelson’s later Jigsaw as the ultimate examples of an IF sub-genre that began a decade before with Sierra’s ambitious but ultimately hopeless Time Zone. It is also the final work of the commercial IF era that I would call an absolute must-play for students of the genre.

Legend had peaked early, but there was still some good work to come. In addition to Meretzky’s Spellcasting series, the company released two games set in the science fictional milieu of Frederick Pohl’s Gateway novels, and one more original work by Bates, a comic fantasy entitled Eric the Unready. Even if it does not again reach the inspired heights of Timequest, Legend’s entire IF catalog is satisfying, well-written, and eminently worth playing today.

As time passed, though, a trend began to assert itself. Legend began to make more and more use of graphics for output and the mouse for input. Legend’s final two IF titles, Eric the Unready and Gateway 2: Homeworld, took advantage of the then-new CD-ROM technology to break up their gameplay with long movie sequences, and abandoned their parsers altogether for the occasional mouse-driven mini-game. My reader can probably see where this trend would ultimately lead. A few months after Gateway 2’s 1993 release, the next Legend adventure hit the shelves. It was based on another literary property, this time Piers Antony’s Xanth series of light-hearted fantasy novels, and the prospective player might not have initially suspected any departures from the established Legend model at all from reading over the box. One she loaded the game up, though, she would find that the text parser had been abandoned at last in favor of the point-and-click model the rest of the industry had gone to years ago. Without a peep of fanfare from Legend or anyone else, Gateway 2 had marked the end of the commercial IF era, the final entry in a line that began with Scott Adams’ Adventureland in 1978 and included several thousand titles in-between.

Legend continued to release point-and-click adventures for another half-decade after giving up on the parser interface. As the nineties wound down, though, it was becoming apparent that graphical adventures were going the way that IF had a decade before, and Legend was acquired by publisher GT Interactive and transitioned into a developer of first-person action-adventure titles. After a few high-profile releases in this genre, the studio was shut down in early 2004. Bob Bates remained at the helm from its birth until its death. As for Steve Meretzky, he designed just one more graphical adventure game for Legend before moving on to other studios and other projects in that genre and others.

Mass-market commercial IF was dead, and (at least as a computer gaming form) may possibly remain so forever, but the genre as a whole would not suffer such a sad fate. The same year that Legend released its two final IF works, an Oxford mathematician named Graham Nelson released a free IF game called Curses that wowed fans of Infocom’s work by being able to stand without shame next to the best of that company’s storied output. Curses, along with Inform, the new programming language Nelson used to create it, would usher in a freeware IF renaissance. The multimedia flashiness of Legend’s work would largely disappear to be replaced by the austere all-text interface of Infocom’s classic period, but what the genre would lose in visual splendor it would gain in literary quality. Freed of the commercial considerations that bound virtually all serious IF authors before them, this new band of hobbyist artists would continue Infocom’s tradition of restless experimentation, and in the process create works that can in some cases stand proudly not just as games but as modern literature. Their story begins in Chapter 8.

Sources for Further Investigation

Games:

Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur. 1989. Bob Bates; Infocom.

Eric the Unready. 1993. Bob Bates; Legend.

Gateway. 1992. Michael Verdu, Glen Dahlgren, and others, based on Frederick Pohl’s novels; Legend.

Gateway 2: Homeworld. 1993. Michael Verdu, Glen Dahlgren, and others, based on Frederick Pohl’s novels; Legend.

Journey. 1989. Marc Blank; Infocom.

Shogun. 1989. David Lebling, based on James Clavell’s novel; Infocom.

Spellcasting 101: Sorcerers Get All the Girls. 1990. Steve Meretzky; Legend.

Spellcasting 201: The Sorcerer’s Appliance. 1991. Steve Meretzky; Legend.

Spellcasting 301: Spring Break. 1992. Steve Meretzky; Legend.

Timequest. 1991. Bob Bates; Legend.

Zork Zero. 1988. Steve Meretzky; Infocom.

Other Works:

Bates, Bob. “Designing the Puzzle.”

http://www.scottkim.com/thinkinggames/GDC00/bates.html.

Berlyn, Mike. “Dumont & Once and Future.” Usenet post to rec.games.int-fiction, June 11 1999.

Briceno, Hector, Wesley Chao, Andrew Glenn, Stanley Hu, Ashwin Krishnamurthy, and Bruce Tsuchida. Down From the Top of Its Game: The Story of Infocom, Inc.

Available online at http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/infocom/info/infocom-paper.pdf.

Granade, Stephen and Phillip Jong. “David Lebling Interview.”

http://brasslantern.org/community/interviews/lebling.html.

Jong, Phillip. “Bob Bates.”

http://www.adventureclassicgaming.com/index.php/site/interviews/168.

Lebling, David. “Offsite Meeting, Wednesday, April 29, 1987.” The Masterpieces of Infocom CD-ROM. Activision: 1996.

Levy, James H. “Gruer’s Profile: James H. Levy.” The Status Line, Summer 1986.

Nelson, Graham. The Inform Designer’s Manual. 4th ed. The Interactive Fiction Libray: St. Charles, Illinois, 2001.

Available online at http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/infocom/compilers/inform6/manuals/designers_manual_4.pdf.

Rosenberg, Ronald. “Computer Games Firm Moving to California.” Boston Globe, May 22, 1989.

http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/infocom/articles/globe.890522.