<<- Chapter 5 Table of Contents Chapter 7 ->>

Chapter 6: The Rest of Commercial IF

English is not English. That became obviously clear at a press conference in London, which was attended by Dave Lebling (Spellbreaker, Starcross) from Infocom and Anita Sinclair (The Pawn) from Magnetic Scrolls.

While chatting we also discussed problems Infocom fans have with the parser of The Pawn. German Infocom User group pointed out that The Pawn does not understand "look into".

Asking Anita about that, she became suspicious for a very short moment, only to counter: "Why should our parser understand this? Look into is completely wrong in English grammar". However, Dave Lebling answered: "In American English "Look into" is a common term." Anita agreed to support "Look into" in future games, even if it conflicts with grammar rules. Vice versa Dave Lebling promised to show more consideration to English people in his next adventure, because Anita immediately complained about a scene in Spellbreaker, in which the parser understands American English, but not British English.

-- Boris Schneider (Happy Computing, June 1987)

Any remotely comprehensive survey of the commercial IF marketplace of the eighties as a whole would necessitate literally hundreds of pages. At IF’s peak around 1983, several dozen companies were actively creating and promoting IF games, which accounted for a significant chunk of the entertainment software market as a whole. Science fiction author Theodore Sturgeon’s famous saying that “ninety percent of everything is crud” certainly applies here, however. If anything, ninety percent is an optimistic figure. Most of the games produced at this time were frankly awful, saddled with borderline illiterate writing, excruciating two-word parsers, and incoherent storylines, while their utter lack of attention to good game design made many well-nigh insolvable for the player who was unwilling to try random actions ad nauseum or hack into the games’ data files for answers. They were all but unplayable in their own time, and today are interesting only as minor historical curiosities.

Amidst all this dross, though, there was a fair amount of quality, or at least interesting, work being done. No other publisher from the era has a catalog worthy of mention in the same breath as Infocom, but there was a handful whose work is worthy of serious discussion today. In this chapter, I will briefly describe the histories of the most significant of the non-Infocom publishers, and discuss some of their most important works.

The Phoenix Mainframe Community and Topologika

Today, Level 9 Computing, which I will discuss shortly, is often referred to as the “British Infocom.” A better candidate for that title, though, might be Topologika, for the origins of its text adventures are surprisingly similar to those of Infocom. The implementers at Topologika were also products of a prestigious university, in this case Cambridge, and their first product was also a microcomputer version of a mainframe game they had developed there. Here their respective stories diverge considerably, however. Topologika’s history and the games it produced are unique and fascinating in their own right.

The mainframe computer at Cambridge was known as Phoenix, and has become something of a legend not only in the IF world but in computer science circles in general. It entered service in 1971, and quickly became a centerpiece of computing research in Britain. It was also the machine on which Jon Thackray and David Seal created what was most likely the first adventure game written outside of America, Acheton, in 1978. As was common in the mainframe world, Acheton was expanded and refined for years after its initial creation, not finally reaching a relatively finished state until 1981. It is yet another variation on the plotless “collect the treasures” fantasy dungeon crawl, but it is distinguished by a number of features. For starters, it is almost incomprehensibly huge, having 403 separate locations to explore, and its difficult is legendary:

Acheton is one of the very earliest adventure games, preceded most significantly by ADVENT (Colossal Cave) and mainframe Zork. It is a game much influenced by those games (there’s even a hollow voice), with the main differences being that it is MUCH larger and (as expected from the Phoenix crew) quite a bit tougher and more cruel. It starts by warning you of its difficulty, and then underscores the point. A smug veteran of Colossal Cave quickly finds the familiar lamp and keys, heads down to that oh-so-familiar grate, opens it up, goes down, falls into a well and dies. This is a wakeup call – and you had better get used to such instant deaths, because there are a lot of them in Acheton (Russotto).

Most importantly, though, the creators of Acheton produced not only a game but a programming environment to allow the creation of more like it. This adventure development system was made freely available to users of Phoenix, and many more games were written with it throughout the eighties.

The home computer explosion prompted some of the Phoenix authors to port their works to microcomputers and seek a publisher for them. Several were published by Acornsoft, but that company soon decided to get out of the adventure game market, and the Cambridge team took their work to a young publisher known as Topologika. A productive, albeit unusual, relationship was soon established. The Phoenix community continued to develop and play games on their mainframe, with the best being ported to home computers and given to Topologika to market. Most were written by members of Cambridge’s Mathematics Department, and play largely as one might expect of games from such creators. They are layered with often difficult but generally fair and logical puzzles, while plot, character, and setting are given a back seat if they receive any consideration at all. While not always terribly interesting from a literary perspective, the games have their devotees even today among lovers of well-designed puzzlefests.

Perhaps Topologika’s most original and satisfying work is Jonathan Partington’s Avon, a full-on immersion into the world of William Shakespeare. The allusions and quotations fly fast and loose as the player deal with characters and situations from Twelfth Night, The Winter’s Tale, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and others:

You are not going to forget today in a hurry.

You will be quite happy just to survive. It started with a trip to Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare's town, and you haven't the slightest idea where it is going to end.

To start with, everything went normally. Like all the other tourists you looked round the town, walked along the banks of the Avon, visited Ann Hathaway's cottage, bought some postcards, had a cup of tea, obstructed the traffic and enjoyed the sunshine. Then something went seriously wrong.

Was it something to do with those three old ladies in the antique shop, the ones who wanted you to buy their old brass cauldron? Did you offend them when you refused? Was there something funny about that pine tree? It made such a strange groaning sound when you walked past it!

Now that you think back, other oddities spring to mind. Were you right in supposing that that ass's head in the museum moved slightly when you passed by?

That strange asp in the pet shop -- it wriggled towards you very purposefully, and it might have bitten you if you hadn't stepped back smartly!

Perhaps most suspicious of all was the behaviour of the pharmacist -- when you walked into his shop to buy some aspirins he hid the phial he was mixing so hastily that you feel sure it was some sort of illicit substance.

The town seemed suddenly rather strange, and definitely menacing, so you decided to take a walk along banks of the river Avon. It was then you knew something, for the streets suddenly looked totally unfamiliar.

Wherever this is, it certainly isn't modern Stratford -- those woods over there remind you of Scotland, the streets might be London, or Egypt, or Venice -- there is nothing that you can get your bearings from.

You took stock of your position. Even the ground at your feet looked unnatural. It was made of boards, as though you were on some sort of stage. You sighed a premature sigh of relief -- surely all was explained: you must be on a huge stage, maybe some sort of film set. Well, that would explain some things, but the whole area looked far too realistic -- those were real trees and real buildings.

Some people passed in the distance, and you heard their conversation: "Marry, 'tis a strange churl, that standeth over there. Methinks it knoweth not the time of day." It was then that hope died and desperation took over -- why, instead of being a warm August day, it had suddenly become a cold winter's afternoon, and it would be dark within a few minutes. Yes, something had gone badly wrong.

So there you are, standing in a world that, although it is definitely NOT Stratford-upon-Avon, does seem to have this strange Shakespearean flavour. To judge by those fragments of Shakespeare's works that you can remember, it all looks very much as though you may have been transported into the world of his plays, but it will be your wits rather than your knowledge that will help you now.

Whoever it was that got you into this nightmare, it is now up to you to find your way back to the present day. Good luck! You are standing on a flat plain. From here it seems that all the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players: they have their exits and their entrances to the north, south, east and west.

:quit

All's well that ends well. Are you sure you want to finish?

?yes

You scored 10 points out of a maximum of 450.

Once more into the breach, dear friend?

?no

Our revels now are ended.

Finished.

Students of literature and lovers of the Bard will have a wonderful time trying to spot all the references, and the game, while no cakewalk, is even much less difficult than the Topologika norm.

Topologika’s work remained almost defiantly quirky over the years, and that, combined with the Phoenix group’s unapologetically elitist, austere approach to game design, caused it to remain something of an esoteric taste even in IF’s commercial heyday. The company stuck with a two-word parser, albeit a fairly good one as such things go, for years after Infocom had raised that particular bar, and common IF shortcuts such as I for INVENTORY were never implemented. Most legendary of all is Topologika’s refusal to implement one of the most common IF verbs of all, EXAMINE. Despite, or perhaps because of, all this, its games have a certain charm all their own for many.

As the eighties drew to a close, the Phoenix community began to disperse, and Toplogika grew less interested in publishing its work in a commercial arena ever more enthralled with graphical adventures. The company still exists today, but only as a publisher of educational software. The old Phoenix mainframe was finally shut down in 1995 amidst a great outburst of tears and nostalgia amongst those for whom it had been an important part of their lives.

Present at Cambridge for many of the glory years of the Phoenix IF community and briefly a student of Jonathan Partington was a mathematics major named Graham Nelson, who would have a huge role to play in the future of IF. We will learn more of him and his work in future chapters.

Level 9 Computing

Level 9 Computing was founded in England by the three Austin brothers – Pete, Mike, and Nick – in 1981. At first the brothers concentrated on utilities and arcade games, but they found their calling, as it were, when they created yet another adaptation of the original Adventure, which they entitled Colossal Adventure to advertise the expanded end-game section that they had included. Today, the game does deserve respect for its technical prowess if not its originality. Level 9’s compression techniques were better even than those of Infocom, and allowed it to pack not only the whole original Adventure but also its expanded end-game into a BBC Micro with 32K of memory and a cassette drive for storage. The company in fact loved to advertise the size of its games compared to the competition, a trend that reached a somewhat ridiculous climax when it breathlessly declared its game Snowball to be the largest adventure ever, boasting 7000 rooms. What was not mentioned was that 6800 of those rooms were part of a huge, featureless maze.

Hyperbole aside, Level 9 produced a considerable number of solid adventures during the eighties. As was quickly becoming the norm among IF developers, the Austins designed their games to run on a virtual machine, know as the A-Code system in their case, to allow them to easily port them to many platforms. Beginning quite early in its history, Level 9 also began including simple line-drawn graphics with some versions of its adventures. Its early games could not rival Infocom in technical or literary polish, but it should be recognized that Level 9’s hardware constraints were also much greater. Because it sold primarily into the British market, where cassettes rather than floppy disks were the dominant storage medium, Level 9 did not have the luxury of using virtual memory techniques to increase the complexity of its efforts. Looked at in this light, the company’s achievements are as remarkable in their own way as those of Infocom. Common consensus in fact holds Level 9’s games to be the most advanced cassette-based adventures ever written. In Britain, Level 9 was the dominant publisher of text adventures for several years, the company that players immediately thought of when the genre was discussed. A whole generation of players cut their teeth on these games in a country where Infocom’s games were usually available only as prohibitively expensive imports, and often required hardware beyond the average Briton’s means.

In 1986, Level 9’s dominance in Britain was being seriously challenged for the first time. The increasing affordability of disk drives and a distribution deal that Infocom had signed with a British publisher meant that Infocom’s games were finally becoming accessible to the average user, and another upstart British company I will discuss shortly, Magnetic Scrolls, was making waves on both sides of the Atlantic. Level 9 responded with an all-new adventure engine named KAOS, which targeted newer, more powerful machines such as the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST and which was the equal of any of its rivals’ technology. The handful of games that Level 9 produced with this system are in fact among the most sophisticated of their era, and quite playable even today.

The most remembered and respected of this group is Pete Austin’s Knight Orc, which, in an unusual reversal, casts the player in the role of the thoroughly disgusting and disreputable character of the title, who at the beginning of the game is “volunteered” by his companions to participate in a joust with a knight. (Volunteering in this context means being tied to a horse that is then led onto the field of combat.)

After this rather deflating experience, the player is off to explore a land full of prima donnas and losers of all ilk. From Robb Sherwin’s review:

So, then. You're an orc trapped in human country. While attempting to pick up some rope to cross the river you will encounter the first bit of magic the game has to offer: the characters. I have never witnessed a greater collection of thugs, losers, egomaniacs and self-important motos than I have in this game. The descriptions offered by the parser as to the wandering characters are cruel --

The gripper: "he is a squinty, rat-like youth, with an orcish squint."

Kris the ant-warrior: "she is a muscle-bound champion, armoured with plates of giant ant cuticle and wearing a strange ant-head helm. She looks a lot like an ogre-sized fried roach."

Denzyl: "he is a right gullible and stupid-looking person."

Fungus the boggit-man: "he is a lanky, twitchy-fingered, nicotine-addict.”

-- but a riot. Efffing genius.

A personal favorite is the Prophet, whom the game uses as an embodiment of the more distasteful aspects of organized religion:

A sweaty pedophile quite happy to swarm on about the meek inheriting the earth, turning the other cheek and the love of you know who… Until you mention liberation theology, disarmament, or anyone other than human males becoming ministers.

These characters and many others wander the landscape of their own accord, and the player must interact with virtually all of them to solve the game. The result is not only one of the most smartly funny games of its era but also a technical tour de force, and features an ending so original and surprising that I cannot bear to spoil it here.

Like most of its contemporaries, Level 9 was ultimately undone by declining commercial interest in parser-based adventures. Its final IF game, released in 1989, was the very unique supernatural crime drama Scapeghost, a classic in its own right almost the equal of Knight Orc. The company struggled on for two more years, attempting to move into other areas of software development, but finally closed its doors in 1991.

Melbourne House

Australian publisher Melbourne House was founded in 1978 with the intention of providing books to the nascent home computer market. From there, the company branched out into software, and in the early eighties acquired the then still modestly priced license to develop a series of IF games based upon J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. A handful of Melbourne University students, most notably Veronika Megler and Philip Mitchell, was hired to create the first of these adventures. Released in 1982 for the ZX Spectrum and subsequently ported to a wide variety of machines, The Hobbit became probably the single most commercially successful IF game ever, selling in excess of one million copies worldwide on the strength of its license and Melbourne House’s extensive promotion. It was often packaged with a copy of Tolkien’s novel, and provided a ticket for entry to his universe for many young players, myself among them. For that perhaps more than anything else the game deserves considerable credit.

On more capable machines of its time, The Hobbit featured a nicely done (for its time) picture of virtually every location as well as even more impressive background music, features that certainly did nothing to diminish its marketability. Today, however, the most interesting feature of the game is its attempt to provide a degree of independent agency to its characters. Thorin, Gandalf, and various others move about of their own accord, occasionally speaking a stock phrase to the player (who of course plays the role of Bilbo), or commenting on the action. The player can even command these characters to do various things, although there is seldom any real point. In truth, this vaunted “artificial intelligence” that Melbourne House loved to hype is more often annoying than useful. On the few occasions where another character is needed, he always seems to have gone wandering off somewhere else, and sometimes the characters’ actions are frustrating in the extreme, as when they pluck items right off the player’s person for no apparent reason and carry them off. Most of the fun to be had with the game actually involves abusing its world model and seeing what strange interactions can be created. The player can for instance in some versions instruct Thorin to pick Gandalf up and carry him about, and he will happily comply for dozens of turns.

Indeed, The Hobbit is more memorable for quirks like this, and of course for its multimedia elements, than for its game design. It follows the basic pattern of Tolkien’s novel, but captures neither its whimsy nor its grandeur. Whole chapters are encapsulated into single rooms that are described in just a few bland sentences. There is no sense of forward motion or plot to the game, just a series of locations representing very simplified versions of scenes from the novel. The trolls’ clearing, for instance, is just two rooms away from Bilbo’s home, to which he can return at any time. Melbourne House made a major promotional point of The Hobbit’s parser, which it dubbed Inglish, but, while it does support more than two words, it is not a patch on Infocom’s contemporaneous parsing technology. In truth, the game receives the coverage it does in this essay more for its enormous commercial success and accompanying role in introducing many to IF than any other quality.

Melbourne House produced three more adventures in the same mold as The Hobbit, covering the three books of The Lord of the Rings. The problematic idea of including active actors remained in place, and was in fact expanded. The player could now at times actually switch roles, whereupon the former protagonist would begin acting with the same artificial “intelligence” as the other actors. All of the problems of the first game – bugs, quirks, and an utter failure to capture the magic of Tolkien’s world – remained, and the games failed to duplicate the commercial success of The Hobbit. Melbourne House had always had its fingers in many pies, and soon abandoned IF development for greener pastures.

Trillium / Telarium

Telarium, which called itself Trillium for its first few games before changing its name due to possible trademark issues, was active in the IF market for only a few years. Its first games were published in 1984, and by 1987 it was defunct. The company was never an entirely independent entity, but rather a subsidiary of Spinnaker Software, a leading publisher of educational software of the time. Telarium was located very close to Infocom’s Cambridge, Massachusetts offices, and was also similar to its rival in packaging its games in fairly elaborate ways, including atmospheric documentation and sometimes even feelies. Indeed, Telarium seems to have been greatly “inspired” by Infocom’s business model, even briefly publishing a free newsletter for its customers similar to The New Zork Times. Unlike Infocom, but in tune with the prevailing trends of the market, Telarium included pictures and occasional sound effects and musical flourishes in its games. Some even contained simple arcade sequences to break the text adventuring monotony. This use of multimedia flash was somewhat ironic considering Telarium’s central conceit: all of its games were either adaptations of literary works or, in a couple of cases, direct collaborations with contemporary print authors on new stories.

The adaptation of a work of linear fiction to an interactive format is always a dicey proposition. Presumably, a good chunk of the game’s audience will be there because they are fans of the book, but many will also have picked up the game on its own merits. If the game’s developers simply recreate the story of the book, those who have read it will know exactly what to do at every turn, thus leaving them with no real challenge, while those who have not will likely have no idea how to proceed. It is also difficult to avoid giving the player the feeling that she is being railroaded, being forced to jump through an improbable and illogical series of hoops to get to each plot event, simply because that is how things happened in the book. (Granted, every game railroads the player to some extent. The trick for the author is giving the player the illusion of total freedom.) Finally, there is the unavoidable fact that most print literature revolves around characters and their interactions, while most IF written even today is object-oriented in the most literal sense, believable character interaction being such a problematic area for the genre.

Telarium dealt with these issues in various ways. One was to choose carefully its source material. One of the books it chose to adapt, Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama, places almost no emphasis on personalities. While a team of astronauts is present and given some superficial characteristics, the novel’s focus is the giant, long abandoned alien spaceship which they explore. This is of course a perfect setup for an adventure game, which perhaps explains why Infocom essentially stole the idea for its own Starcross before Telarium’s official adaptation. Telarium was able to do a fairly “straight” conversion of the novel, inserting text adventures puzzles here and there to challenge the player, and have the whole thing work as a solid, albeit unexceptional, adventure game. In other cases, Telarium placed its games in the same settings as their source novels, but told somewhat different stories, as in its adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, which takes up the story of Fireman Guy Montag just at the conclusion of the events of the novel. The result is a decently designed science fiction adventure that just happened to have Bradbury’s name on its box. Telarium’s work is most interesting, though, when it confronts issues of character interaction head-on, which it does twice: in its adaptation of Roger Zelazny’s fantasy novel Nine Princes in Amber, and in its interactive Perry Mason mystery, The Case of the Mandarin Murder.

Zelazny’s novel, the first of a series of ten of generally declining quality, is told from the perspective of Corwin, one of nine princes of the magical land of Amber, the one true world of which all other realities, including our own, are but shadows. The brothers’ father has disappeared, and his sons are left feuding amongst themselves over who will assume the Kingship, or for that matter if anyone should at all until the King is confirmed dead. A bewildering, Machiavellian series of plots and counter-plots ensues. The novel is a classic, with its own street-smart flavor that is miles away from the typical Tolkien knock-off that all too often defines the fantasy genre. With its emphasis on personalities, it is also one of the last works one would immediately imagine being adaptable to IF. Telarium deserves credit for sheer chutzpah if nothing else. Indeed, the game’s team of twenty or so authors studiously avoids easy solutions like those employed by the Fahrenheit 451 team, choosing instead to chronicle the events of the novel in a fairly straightforward fashion. To facilitate character interaction, a bewildering list of communication verbs is provided in the documentation. The player can, just for starters, “snarl,” “flatter,” “calm,” “spit,” “bribe,” “wink,” or “plead.” Upon reading this, the prospective player might think he is in for a revolutionary IF experience. Unfortunately, actually playing the game leads to inevitable disappointment. While these verbs are indeed understood by the game, there is never any sense that the player is engaging in meaningful discourse with the other characters. Rather, he must determine exactly what will lead to the plot advancing and, of course, Corwin surviving. The conversation system is actually more of an elaborate guess-the-verb puzzle than a simulation of real communication, and the solutions are all too often arbitrary, reachable only through extensive trial and error or – more efficiently – through having read Zelazny’s book. Things do get a bit more flexible toward the end of the game, where the player can summon any of several different endings depending on how he plays the last few conversations, but it is nevertheless a bit hard not to feel let down by all the game promises and then fails to deliver. One suspects that the development team truly hoped to create the flexible system described in the documentation, but were ultimately undone by hardware constraints and all the limitations of IF character interaction that authors still struggle with today. What they ended up with is not a bad game – in fact, it is one of Telarium’s best, and working out the conversational “puzzles” can actually be oddly satisfying at times – but they seemed to be aiming so much higher.

Telarium’s Perry Mason game works better, albeit only marginally so. Although Erle Stanley Gardner’s name was prominently featured on the box, the game is not directly based on any of his novels, and in fact its protagonist is the gentleman Perry Mason of the television series rather than the edgier version found in Gardner’s print work. The game even follows the structure of a typical television episode, although the “script” is original to Telarium. The player is briefly introduced to a new client, a beautiful (naturally) young lady named Laura Kapp, who fears that her husband Victor, a prominent local restaurateur, is about to divorce her due to malicious rumors. The next day, Victor turns up dead, and Laura is of course the prime suspect. The game is on, as Perry must prove her innocence against all odds. After he has searched the crime scene for evidence, the heart of the game really begins with the trial. Perry’s loyal assistants Paul Drake and Della Street are both present, and the player must ask them to investigate various leads while he performs in the courtroom, questioning the various witnesses and occasionally objecting to the prosecution’s lines of inquiry. To facilitate this, the game supports a similarly wide range of conversational verbs to those of the Amber game. Also included in the manual is a list of phrases that the player can combine together to build quite complex questions to ask the witnesses. Once again, however, all of this looks more impressive in theory than it actually plays out in practice. The game rarely manages to convince that the player that he is having a real, organic exchange. Once again we are left with just a series of elaborate conversational puzzles that the player must work out through logic, intuition, and good old trial and error. For all that, though, Perry Mason is a surprisingly satisfying game to play. Mapping out the correct path to a conviction is challenging and rewarding. To succeed, the player must not only deal with his witnesses in the right way in court, but also use Paul and Della’s talents in the right way and at the right time. The game even provides multiple endings of a sort. Raising enough doubt to acquit Laura is not hugely difficult, but acquiting Laura and also bringing the real murderer to break down and confess in court is another proposition altogether. Even some of the more useless conversational commands can be entertaining. It is good fun to WHIRL on a jumpy witness in the courtroom and otherwise grandstand for the jury, even if there is no strict point to it from the standpoint of the game’s internal logic. The whole thing adds up to a game experience that is completely unique in IF, and indeed one of the most interesting potential pathways for further exploration in the genre.

A comparison of the Commodore 64 and IBM PC versions of Nine Princes in Amber

While Telarium’s reach often exceeded its grasp, most of its games nevertheless stand up fairly well today, although I do heartily recommend that the interested reader seek out the Commodore 64 versions to play on an emulator. While versions were created for MS-DOS, the graphics and sound therein are so aggressively ugly that they all but ruin the games. The Commodore 64 versions on the other hand, while hardly state of the art, do retain a certain colorful, retro charm. Also of potential interest is Spinnaker’s Windham Classics children’s software label, which created two IF games in the Telarium mode: adaptations of the children’s classics Treasure Island and The Swiss Family Robinson.

Synapse’s Electronic Novels

Synapse Software was already well established as a maker of arcade-style games when it chose to enter the IF market in 1983. The company went all out to emphasis the literary qualities of its work, subtitling the games “Electronic Novels,” packaging them to appear like a hardcover book, and including within each a substantial novella setting up its premise. It sought out established print authors to write the text for its games, which were then programmed by the Synapse technical team. Technologically, Synapse took dead aim at market leaders Infocom. It was something of an open secret in the industry that its parsing system, known as BTZ, stood for “Better than Zork.” In a contemporaneous interview, Synapse developer Richard Sanford trumpets the company’s parser:

"No parser can handle the language and resolve all ambiguities, so we came up with something else, a keyword concept based on certain built-in filters. We do as much of that [conventional parsing] as possible, but we may only have to parse part of a command and leave the rest to the filters. They look to see how a phrase involving a keyword object might tend to have meaning in this fictional world (the context of the game)."In Mindwheel and Essex, the first games in the series, this keyword approach enables the reader/player to converse with other characters in ways no other adventure has ever permitted. You can elicit reasonable responses to questions like: "Thug, what lies east of here?" for example, or "Singer, how can you help me?" "There are aspects of the Eliza approach that we've used as part of an eclectic combination of tools," Sanford continues, "and we couldn't do it without BTZ, which is responsible for codifying and assembling - pairing nouns with verbs, checking for prepositions and conditional modifiers such as adjectives and adverbs." Sanford says "the parser is still being refined, and will continue to be refined. Right now, there are certain ambiguities with combinations in compound sentences. We're cleaning up things like this and trying to make it even smoother" (Addams, “if”).

All in all, there is a bit too much hyperbole not only in statements like this but in almost everything Synapse produced. Its parser was not bad for the era, but was most certainly not the equal of Infocom’s, and its games are a bit of a frustrating lot overall. For all their well-developed premises and aggressively literary approach to a genre still generally referred to as humble text adventures, their design as playable games often left something to be desired. As much as some may desire to see IF accepted as a viable literary form, they must also recognize that all the wonderful prose in the world is ultimately wasted if the reader / player cannot easily interact with the creation within which that prose resides. One unfortunately often get the impression when playing its games that Synapse did not see this basic truism, and its products often suffer for it. The end result is excruciatingly frustrating for one who desires to see IF go in exactly the literary direction Synapse was pursuing, and sees it coming so close to a certain IF Holy Grail, only to be undone by poor design decisions.

Just as annoying as the fundamental game design flaws is the real-time interface employed by all of Synapse’s works. If the player does not type something in an allotted amount of time, a turn passes in the world of the game. The idea does not work any better for Synapse than it did for Infocom in its own later real-time experiment, Border Zone. Real-time interaction is fundamentally at odds with the book-like nature of IF, and it is surprising that so many designers have chosen to go down this particular rabbit hole over the years.

The best work to come out of Synapse was Robert Pinsky’s Mindwheel. Pinsky is one of the most “high-brow” literary figures to have associated himself with IF. At the time of the game’s development, he was already a very respected young poet. Since then, he has won considerable fame not only as a poet in his own right but also as a translator of Dante’s work into English and as the poetry editor for the online magazine Slate. Pinsky, although hardly a technophile himself, has remained consistently optimistic about the possibilities for computer-mediated literature. It was thus rather appropriate that he served as poet laureate of the United States during the biggest years of the Internet boom, 1997 to 2000.

Appropriately enough for a game authored by a translator of Dante’s Inferno, Mindwheel is a very metaphysical work. The player is tasked with retrieving a mysterious artifact known as the Wheel of Wisdom. To do so, she must travel into the minds of four different people:

"BOBBY CLEMON, assassinated rock star, once called 'half John Lennon and half Janis Joplin'. This charismatic, scandalous musician made the anthems of freedom and pleasure for a generation. Shot by an unknown attacker during an immense protest rally.

"THE GENERALISSIMO, dictator and war criminal. He was executed for crimes so horrible that it seemed for a time that such hatred and violence had vanished from the world. But incredibly, this monstrous genius now has a considerable posthumous following.

"DOCTOR EVA FEIN, 'the female Einstein' of the Late Technological Age.

Honored for earthshaking work on the nature of matter and energy. A

schoolmate of THE GENERALISSIMO, she fled his regime, then developed the horrible weapons that defeated him -- weapons that now threaten the

obliteration of all life. Her deathbed message to the world supplied BOBBY CLEMON with the words of a peace song.

"THE POET, passionate, many-minded genius of the Learning and Art Era, he wrote the great War Trilogy of poetic dramas, which centuries after his death remain the glory of your planet's literature. He wrote the plays in hopes of making enough money to marry the young princess he was hired to tutor. Her father, discovering the romance, had THE POET put to death in the Royal Dungeons.”

Not surprisingly, much of Mindwheel revolves around words and poetry. Finishing it requires that the player answer various riddles and complete a number of sonnets using words inside found about the varied consciousnesses she explores. The worlds it presents are surreal, often beautiful, and usually fascinating. Pinsky’s prose is a consistent joy to read, and he makes a compelling scenario out of a premise that would have likely resulted in a pretentious mess in the hands of a lesser writer. (Indeed, several recent IF efforts have attempted something similar to Mindwheel, and ended up with just that.) Unfortunately, far too many unmotivated, random actions are required of the player, and the game continually stymies her sense of wonder with mundane text adventure puzzles. One senses that Synapse, not only in this work but in all its games, wanted to create something akin to Infocom’s A Mind Forever Voyaging, but lacked the courage to fully embrace the narrative at the expense of the crossword. Gamelike elements are certainly not the death knell to a work’s potential literary value, as lasting classics like Trinity prove, but in this case the puzzles seem grafted onto the narrative out of some misguided sense of obligation. The result is a tantalizing, fascinating work, but one that is far too frustrating to really play without outside guidance. Still, Mindwheel is so unique and well-written, and so compelling when it works, that I have to recommend that anyone seriously interested in the literary possibilities of IF make time for it. I would also emphasize, of course, that there is no shame in consulting a walkthrough.

Given time, Synapse might very well have sorted out its teething problems with design. Unfortunately, though, its electronic novel series ended up being a short-lived effort. Although Mindwheel did fairly well on the strength of some good mainstream press, sales of the other three titles were rather abysmal. It would appear that the computer game market did not know quite what to do with such a forthrightly literary approach to text adventures. It certainly could not have helped the electronic novels’ fate that they were all text at a time when virtually everyone working in IF, with the exceptions of Infocom and niche publisher Topologika, was now including multimedia elements of one kind or another in their games. Being the market leader with an established fan base, Infocom would be able to get away with selling text-only games for a few more years, but Synapse’s attempt to break into the IF market with such unflashy products was perhaps doomed to failure from the beginning. Reports are that three more electronic novels were virtually complete when Broderbund Software, which had acquired Synapse in late 1984, shut the whole project down in 1986.

Electronic Arts’ Amnesia

Electronic Arts, one of the biggest producers of entertainment software of the eighties, as indeed it still is today, published only one work of IF. That work, Amnesia, was however quite high profile in its day, having been written by respected science fiction author and poet Thomas M. Disch. True to its title, the game has the player wake up naked and alone in a hotel room in present-day Manhattan, with no memory of who he is or how he got there. The amnesia gambit has become something of a tiresome cliché in contemporary IF, but here Disch plays it to the hilt and makes it work. The opening sequence brings the player’s memory loss home in a clever way, by subverting a sequence that on first play seems to be allowing the player to customize his character:

You wake up feeling wonderful.

But also, in some indefinable way, strange.

Slowly, as you lie there on the cool bedspread, it dawns on you that you have absolutely no idea where you are. A hotel room, by the look of it. But with the curtains drawn. You don't know in what city, or even what country.

Then the blank of WHERE AM I? balloons into the bigger, the total blank of WHO AM I? It's a question without an answer. Your memory is an open book – with every page blank. You have no name, no known address, no memories of friends or relatives, or schools or jobs. You have ...

Thomas M. Disch's

AMNESIA

Hotel Room

What's a person to do in such a situation?

What YOU do is....

>stand

You get out of bed, and as you do, you realize, from a glance at your naked body, that you are white, male, and reasonably well-put-together. But what about your face? That's part of anyone's identity that should be proof against amnesia. The mirror over the dresser is angled so you can't see yourself from where you stand. So you decide to take a simple test, closing your eyes and taking an inventory of how you think you OUGHT to look.

Your hair -- is it light or dark?

>light

Is it long or short?

>short

Do you have a beard? Or a moustache? Or neither? Or both?

>neither

What is the color of your eyes?

>brown

You could hardly be more completely mistaken! For when you look into the mirror, the stranger you see there has long blonde hair. He has a full beard. And his eyes are emphatically blue.

In a sense, of course, this sequence does allow the player to customize his character. It is just that the end result will be the opposite of the choices that he makes.

Amnesia’s strengths and weaknesses are remarkably similar to those of the Synapse games. The mystery at the heart of the game is compelling, as, after solving the game’s first few puzzles to acquire clothing and escape from the hotel, the player finds mysterious people attempting to kill him as he wanders Manhattan searching for clues to his identity. Disch handles this plot with all the skill of a seasoned professional, and the player is left feeling deeply driven to figure out just what is going on here.

Unfortunately, the game’s many annoyances make appreciating its more compelling aspects somewhat difficult at times. At its heart is a sophisticated simulation of Manhattan – all of it, encompassing some 4000 separate locations. Luckily, a map is included in the game’s documentation. Even the subway system is simulated realistically, the trains moving about from station to station. Riding the subway costs money of course, as does eating and renting a room to sleep in at night, both of which the player is required to do occasionally if he is not to drop dead in the street. The player can acquire money in various ways: by panhandling, by doing odd jobs such as window washing, or course of by outright theft. Regardless of the approach he chooses, however, one thing holds true: none of this is any fun. It is but dull busywork that the player must slog through in the hopes of occasionally getting the opportunity to advance the compelling central plot that he actually cares about. Player Phil Goetz explains further:

I have devoted several days to trying to play Amnesia. I say "trying to play", because what I did could not well be described as playing. It was more like trying to write something in a language for which you only have a few cryptic system man pages. I spent all my time finding food and a place to sleep, and so never got to go anywhere or solve anything. Furthermore, the map was so damned big, with no indication of where to go, that I calculated that at my present rate of exploration it would take months of full-time play to visit the whole map.

Playing was never so much work. I honestly think Amnesia

is for

those reasons the worst game I ever paid money for. This

despite the fact

that it may be technically the most sophisticated text adventure

released

professionally.

The end result may be a depressingly accurate simulation of real life, but it works as neither game nor literature. Amnesia is a remarkably sophisticated simulation, and its creators have the right to be proud of it just on its technical merits, but its misguided simulational aspects have the distinct whiff of something that was more fun to program that it is to actually play. It also stands as a warning to authors today of what can happen if they allow the simulation aspects of their games to run rampant and overwhelm the narrative qualities.

Released in 1986, Amnesia was one of the last commercial all-text titles to emerge outside of Infocom, and was, perhaps unsurprisingly, not a hit with either reviewers or the general public. Disch had positively gushed about the possibilities of interactive literature before Amnesia’s release, but in the end was left thoroughly disappointed and embittered by the whole experience. Certainly some of this was due to technical limitations of the time, which made the end result only a shadow of his initial vision. Even though it stands as one of the most ambitious titles of the commercial era, the final game reportedly contains only about half the text that Disch had hoped to include. As for the game’s commercial and critical failure, Disch blamed the audience for being incapable of appreciating his genius: “trying to impose over this structure a dramatic conception other than puzzle was apparently too much for the audience” (McCaffrey). While the authors at Infocom and many other companies might have undoubtedly shared some of Disch’s frustrations with trying to sell works of interactive literature into a computer game marketplace, Disch overlooks his own failures of vision in statements like this one. Disch himself failed to honor his “dramatic conception” in Amnesia, imposing over his compelling plot a layer of annoying, simulationist puzzles, and this is the work’s ultimate downfall. The sad fact is that Amnesis received at the hands of the marketplace the fate it deserved.

Our experiences with Synapse’s work and with Amnesia have shown that involving professional authors of static fiction by no means guarantees a compelling work of IF. A prospective IF writer must master not only the standard prose techniques for plotting, characterization, and description, but also must exercise good game design judgment. Seeing this battlefield strewn with the wreckage of their more high-profile competitors, as it were, makes the literary achievements of Infocom’s humble hackers in works like A Mind Forever Voyaging and Trinity seem all the more remarkable.

Magnetic Scrolls

London developer Magnetic Scrolls arrived with a bang in 1986 when its first game, The Pawn, hit the market on several computer systems at once. There was nothing terribly original about the The Pawn’s plot or gameplay. The player wakes up following a blow to the head in the fantasy land of Kerovnia, where she must perform various tasks for various characters – from whence arises the game’s name -- in order to find her way home. The occasional self-referential and distinctly British nugget aside, such as a dwarf campaigning for mayor with the promise to “rid dungeons of mazes of any sort,” none of this is terribly inspiring. Few reviewers paid much attention to The Pawn’s rather threadbare plot, however, or to its gameplay, a curious and frustrating mixture of obvious and hopelessly obscure puzzles. The Pawn rather caused the sensation it did because it married its stock text adventure premise to a series of quite nicely done high-resolution pictures and, on the newer generation of 16-bit machines, a slick interface that allowed the player to arrange the screen in various ways and perform some functions using the mouse. The game also featured some very nice music on suitably capable machines. Even on smaller machines, none of this flash seemed to take away from the game’s core parsing technology, which, if not quite up to par with Infocom, was better than just about anything else out there. Magnetic Scrolls in fact advertised the game’s parser almost as heavily as its graphics, emphasizing its ability to understand such tortured constructions as, “Get all except the cases but not the violin case then kill the man-eating shrew with the contents of the violin case.”

Magnetic Scrolls and The Pawn might have seemed to have sprung out of nowhere, but the company had actually already been in business for two years in 1986, having been founded by Anita Sinclair and several partners with the intention of making an adventure game for the brand new Sinclair QL computer. (Anita was friendly with but unrelated to Clive Sinclair, the eccentric British inventor behind the Sinclair line of home computers.) The Pawn was released as a text-only game for the QL in 1985, but the computer and Magnetic Scrolls’ game were both utter flops in the marketplace. Only at this point did Magnetic Scrolls decide to add graphics to its game and port it to other, more successful machines. While its graphics were unique, in many other respects Magnetic Scrolls copied the Infocom model, developing The Pawn on a VAX mainframe and then porting it to microcomputers via a virtual machine similar to Infocom’s Z-Machine. Plainly, Magnetic Scrolls was following Infocom’s lead in investing in the tools and infrastructure right from the start that would allow it to produce a regular stream of text adventures. While the computer game press continually tried to concoct a bloody rivalry between the two companies, in truth they were quite friendly with one another. The occasional cultural exchange visit occurred, and there were even discussions of the two houses working together on collaborative efforts, although they ultimately went nowhere.

Magnetic Scrolls was quite the phenomenon in the press during this early period. A series of in-house exposes were published in the major gaming magazines of the day, as one scruffy geek reporter after another fell in love with the company’s secret weapon, the young, charming, and very comely Anita Sinclair.

The Pawn became a major commercial hit, and its follow-up, Guild of Thieves, did almost as well. Guild is the most successful of Magnetic Scrolls’ works as a playable game. Set in the same fantasy land as The Pawn, it casts the player as an apprentice member of its titular organization, who, in order to achieve full membership, must prove her worth by robbing a castle and its surrounding landscape blind. The plot never develops beyond that. The game is a thematically unambitious collect the treasures romp in the mode of Adventure and Zork, but it succeeds by charming the player with its skewed British sense of humor and by offering a perfectly balanced progression of puzzles. The early stages are almost trivially easy, but the difficulty ramps up steadily, so that finishing is a real accomplishment. There are a few slightly dodgy puzzles, but on the whole the game is fair if, especially in its ending stages, unforgiving, and offers one of the best implementations one can hope to find of this old-school type of text adventuring. It is also very large, offering the player plenty of value for her money.

Magnetic Scrolls produced three more games using the same engine as The Pawn and Guild of Thieves. The company confined itself consistently to text adventures as opposed to interactive literature, being largely content to offer the player a collection of puzzles wrapped around some tasteful graphics and a solid dose of the humor it quickly became known for. Its only attempt to break away from light-hearted fantasy, and its most interesting (although deeply flawed) effort, was Rob Steggles’ Corruption. Steggles had already done most of the writing for The Pawn and Guild of Thieves when he decided, to paraphrase Monty Python, to do something completely different. Corruption takes place in (then) present-day London. The player is a young up-and-comer in The City, who has just been promoted to partner of his law firm when he finds that his employers do not, to say the least, have his best interests at heart. They are actually planning to frame him for insider trading transactions they themselves committed. That is not all, though. They are also running a cocaine-smuggling ring, and one of them is having an affair with the player’s wife. The game takes place over a single day, with each turn counting for one minute, and its object is of course to clear the player’s name and bring the real guilty parties to justice. With its plot involving insider trading and financial misdeeds, Corruption is as perfectly of its time as Trinity. It was released in 1988, as the American savings and loan scandal was in full flight and just after the movie Wall Street appeared to engrave forever into the popular lexicon Gordon Gecko’s catch-phrase, “Greed is good.”

The game is quite complex, having some of the flavor of the early Infocom mysteries but on a more ambitious scale. While its geography is fairly confined, a surprising number of characters move about it with independent agency. The player must take just the right steps, firstly just to avoid the various snares that are set for him and later to bring the game as a whole to a satisfactory conclusion. Doing so requires constant learning by death and failure, but at least at first this is not so egregious if approached in the right frame of mind:

Corruption is a giant riddle, and to decipher its meaning, you must play, and replay, each of its parts. Once the player has mapped out the movements of the non-player characters, he will recognize a web of deceit and betrayal, and be able guide his character to paths that lead to a satisfying ending (Sandsquish).

Thus the player engages in a sort of meta-narrative, learning more about the mystery and the characters involved and generally probing the boundaries of the simulation by sacrificing his pawn – the player’s alter ego – over and over in return for information he will eventually use to map out a successful path through the story. Although modern IF theory generally condemns this emphasis on learning by death, in certain cases it can work. Corruption ultimately frustrates not through this sin, if indeed sin it be, but by failing to adhere to reasonable rules that might give the player a fighting chance of actually solving it by this method. There are far too many tiny details that show up in one location for a bare handful of turns, and too many arbitrarily exact choices the player must make. Corruption is one of the cruelest games one will ever play. At one point it actually awards the player points for going down a dead-end path. Since the player will assume, based on all his previous IF experience, that that point reward means that he is onto something important, he will likely spend many frustrating hours beating his head against this proverbial brick wall. Such bizarre design “features” as this may represent fragments of alternate paths that could not ultimately be implemented. In the end, though, they inevitably cause the player to lose faith in the game. Magnetic Scrolls was kind enough to include a hint booklet with this and all its games, rather than force the player to purchase it separately as did Infocom and many others, but this is small substitute for the satisfaction of solving a game on one’s own. Like too many games of its era, Corruption comes close to genius only to fall down not in its abstracts but in the nitty-gritty of its execution.

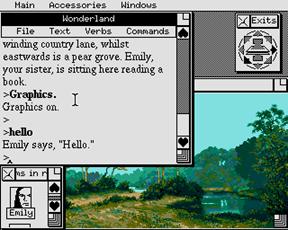

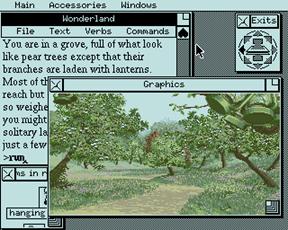

The three games that followed The Pawn and Guild of Thieves, Corruption among them, were nowhere near as successful as their predecessors. The glow that had accompanied Magnetic Scrolls’ initial entry into the market had faded, and the larger industry trend away from parsers and toward point and click interfaces could not be fought for long. Magnetic Scrolls decided that what was needed was an even more elaborate graphical interface overlaid on the basic IF model, and spent a great deal of time and money developing a new system, which it called Magnetic Windows. In games running under this system, the player can arrange a variety of windows on the screen to suit her purposes, and can avoid typing altogether if she so desires. For instance, she can pull up a verbs menu listing all of the actions the game understands, and use this in conjunction with other menus listing all objects in the player’s current inventory and all objects visible in the room she currently inhabits to construct sentences. She can even pull up descriptions of items in an individual window which she can keep on-screen for easy reference. Pictures of the scenery, always Magnetic Scrolls’ trademark, also continued to appear of course, albeit now in their own windows that the player can manipulate as she chooses. The whole is one of the most ambitious IF interfaces ever designed, and while its baroque complexity is undoubtedly not to all tastes, even those people have little to really complain about. By simply shutting all of these bells and whistles off, a Magnetic Windows game can be made to play just like a title in the traditional Infocom mold.

Unfortunately, this impressive new technology saw only limited use. Just one new game was released for Magnetic Windows, an entertaining if rather workmanlike adaptation of Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland novels. Three of Magnetic Scrolls’ older efforts were also re-released in one package as Magnetic Windows games, but sales were not what the company had hoped for. Having spent far too much developing Magnetic Windows and Wonderland and with not enough revenue coming in, Magnetic Scrolls closed up shop in 1991.

In the end, Magnetic Scrolls released only half a dozen games, but its work is much remembered and appreciated today, perhaps more so than any other company’s with the exception of Infocom. This commentator must say that in his opinion its games are often somewhat overrated, although there is certainly considerable entertainment to be found therein. The virtual machine used by the company has been reverse-engineered in a similar fashion to Infocom’s Z-Machine, and interpreters are now available for many different computers to play them. Perhaps this easy accessibility has contributed to them remaining so much in the IF public’s consciousness.

As the eighties drew to a close, virtually all of the publishers of IF were either out of business, teetering on the edge of same, or had left IF for other areas of game development. The marketplace was changing, and even Infocom was not immune. We will take up the sad story of that giant’s downfall, as well as the story of the last active publisher of commercial IF, Legend Entertainment, in the next chapter.

Sources for Further Investigation

Games:

Acheton. 1981. Jon Thackray, David Seal, and Jonathan Partington; Topologika. Released as freeware and available at

http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/phoenix/games/pc/Acheton.zip.

Amnesia. 1986. Thomas M. Disch; Electronic Arts.

Avon. 1985. Jonathan Partington, borrowing characters and situations from William Shakespeare; Topologika.

Released as freeware and available at http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/phoenix/games/pc/Avon.zip.

Colossal Adventure. 1983. Mike Austin, Nick Austin, and Pete Austin, based on Adventure by Will Crowther and Don Woods; Level 9.

Corruption. 1988. Rob Steggles; Magnetic Scrolls.

Fahrenheit 451. 1984. Len Neufeld and Byron Preiss, based on Ray Bradbury’s novel; Telarium.

Guild of Thieves. 1987. Rob Steggles; Magnetic Scrolls.

The Hobbit. Veronika Megler and Philip Mitchell, based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel; Melbourne House.

Released as freeware; versions for many computers are available at http://www.lysator.liu.se/tolkien-games/entry/hobbit.html.

Knight Orc. 1987. Pete Austin; Level 9.

Mindwheel. 1984. Robert Pinsky; Synapse.

Nine Princes in Amber. 1985. Staff of Telarium, based on Roger Zelazny’s novel; Telarium.

The Pawn. 1986. Rob Steggles; Magnetic Scrolls.

Perry Mason: The Case of the Mandarin Murder. 1985. Paisano Productions, based on Erle Stanley Gardner’s character; Telarium.

Rendezvous with Rama. 1984. Ronald Martinez, based on Arthur C. Clarke’s novel; Telarium.

Scapeghost. 1989. Pete Austin, Sandra Sharkey, and Pete Gerrard; Level 9.

Snowball. 1983. Mike Austin, Nick Austin, and Pete Austin; Level 9.

The Swiss Family Robinson. 1984. Staff of Windhim Classics, based on Johann David Wyss’ novel; Windham Classics.

Treasure Island. 1985. Ann Weil and Lee Jackson, based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel; Windham Classics.

Wonderland. 1990. David Bishop, based on Lewis Carrol’s novels; Magnetic Scrolls.

Other Works:

Addams, Shay. “if yr cmptr cn rd ths…” Computer Entertainment, August 1985.

http://www.csd.uwo.ca/Infocom/Articles/parser-war.html.

Addams, Shay. “The Pawn: England’s Finest Hour.” Commodore Magazine, July 1987.

http://www.if-legends.org/~msmemorial/articles.htm/cm787.htm.

Farmer, J.J. Review of Scapeghost. SPAG #6, July 26, 1995.

http://sparkynet.com/spag/s.html#scapeghost.

Forman, Christopher E. Review of Amnesia. SPAG #9, June 11 1996.

http://sparkynet.com/spag/a.html#amnesia.

Goetz, Phil. “Re: Vocabulary Size in Infoocom Games (OOPS! Made a Mistake!)”. Usenet post to rec.arts.int-fiction. March 23, 1992.

Granade, Stephen. “History of Interactive Fiction: Level 9.”

http://www.brasslantern.org/community/history/level9.html.

Granade, Stephen. “History of Interactive Fiction: Topologika.”

Hewison, Richard. “Level 9: Past Masters of the Adventure Game.”

http://www.sinclairlair.co.uk/level9.htm.

Jones, David. Review of The Hobbit. SPAG #38, September 28, 2004.

http://sparkynet.com/spag/h.html#hobbitmh.

Karsmakers, Richard and Stefan Posthuma. “An Interview with Magnetic Scrolls’ Anita Sinclair.” ST News, August 1989.

http://www.if-legends.org/~msmemorial/articles.htm/stnews4v4.htm.

McCaffrey, Larry. Interview with Thomas M. Disch. Across the Wounded Galaxy: Interviews with Contemporary American Science Fiction Authors. University of Illinois Press: Urbana, 1990.

Mirapaul, Matthew. “An Approach to Poetry That Rhymes with HTML.” New York Times, April 3, 1997.

http://partners.nytimes.com/library/cyber/mirapaul/040397mirapaul.html.

Montfort, Nick. Twisty Little Passages. MIT Press: Cambridge, 2003.

Nelson, Graham. “Announcing: Fyleet, Crobe, Sangraal.” Usenet post to rec.arts.int-fiction, August 24, 1999.

Russotto, Matthew T. “Acheton.” Usenet post to rec.games.int-fiction, September 10, 2000.

Sandsquish, Walter. Review of Corruption. SPAG #21, June 15, 2000.

http://sparkynet.com/spag/c.html#corruption.

Schmidal, Gunther. “Gunther Upon Avon.” IF Review, November 24, 2001.

http://www.ministryofpeace.com/if-review/reviews/20011214.html.

Sherwin, Robb. Review of Knight Orc. SPAG #15, October 11, 1998.

http://sparkynet.com/spag/k.html#knight.

Schneider, Boris and Heinrich Lenardt. “Small Talk with Anita.” Happy Computer, January 1987.

http://www.if-legends.org/~msmemorial/articles.htm/hc187.htm.

Steggles, Rob. “Magnetic Scrolls Memories.”

http://www.if-legends.org/~msmemorial/articles.htm/robmemory.htm.

<<- Chapter 5 Table of Contents Chapter 7 ->>