Chapter 3: Bringing IF Home

“I’m in a temple” is as detailed as it gets, but Adams’ games are

distinguished by weirdly errant grammar, a wide vocabulary,

and a talent for arranging diverse objects in a room to

portray it.

-- Graham Nelson (2001)

Even as Adventure was taking the world of institutional computing by storm, another revolution was beginning. Computers were coming home. In 1975, the first commercially available microcomputer arrived. For $397, the hobbyist could purchase an Altair 8800 in the form of “a box of parts, circuit boards, and some poorly written instructions” (Veit). If he was handy with a soldering iron and had luck on his side, several hours labor would yield a functional computer with 256 bytes of memory and an input-output system consisting of a bank of toggle switches and a row of lights. The new technology advanced quickly. By 1978, Altair was already long gone, but several other companies had stepped into the breach to offer relatively practical, usable home computers that even came pre-assembled. Most of these machines had fairly similar capabilities, including perhaps 16 kilobytes of memory and a simple 8-bit microprocessor. Audio cassettes were used for storage. The average cellular phone today possesses vastly more computing power, but in their day these machines were little marvels, and the idea of having a computer of any description available for hacking in the home was a dream come true for a whole generation of hobbyists. Many justifications for their purchase -- word processing, education, and home finance among them -- were offered to spouses and parents, but once the machines were in the home many turned their attention to making them play games.

Since Adventure was the hit of mainframe world at the time, it was only natural that many would seek to bring similar games to the home computer. This was however a rather daunting prospect given the current technology level of home computing. Primitive as it is by the standards of modern IF, Adventure was still vastly too complex to fit into the miniscule memories of this first generation of machines. Those who took up the challenge of bringing IF home would be forced to trim away every unnecessary word in their games and use every clever hack available to save memory. The first to succeed in bringing a playable work of IF to the home computer was Scott Adams.

Scott Adams and Adventure International

In 1978, a little game called Adventureland arrived on the miniscule Tandy TRS-80 entertainment software scene. It borrowed its theme from the mainframe Adventure, requiring the player to collect a number of treasures in a Tokienesque landscape, but its implementation made the earlier game look positively lush and user-friendly. Adams described its inspiration thus:

…soon Mr Adams was captivated by Colossal Caves and Adventure. “I saw the games on a mainframe, and I was fascinated. I owned a Tandy Model I and thought 'let's see if I can write an Adventure type game on the TRS80'. I didn't listen to the people who said it would be impossible to get a program which existed on megabytes of storage into a 16K machine” (Kidd).

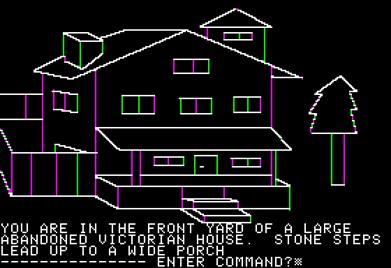

Locations were described not with one or two lines, as in Adventure, or but rather one or two words, and conveying one’s intention to its extremely primitive two-word parser was often more difficult than actually working out how to solve the puzzles the game presented. The game’s engine was written in BASIC rather than assembly code, meaning it was not even able to take full advantage of the primitive hardware on which it ran.

A typical screen from Adventureland (1978)

Primitive as his creation was, Adams was quite clever in choosing to develop Adventureland not as a single, stand-alone program but rather as a game file which is run on an interpreter on the target machine. Adams:

“I didn't try and take the existing program and put it into 16K, but sat down and wrote an adventure language of my own for the machine - an interpreter - and proceeded from there to write an adventure in that language. As a system programmer I know how to write tools. The first tool was the adventure language, the second was the interpreter to understand the language and the third tool allowed me to develop a database for the interpreter to understand” (Kidd).

This model is still used for most IF today. The approach conferred to Adams two major advantages. First, he could develop his games more quickly, since he was not forced to constantly rewrite portions of the code that would remain the same from game to game; and second, he could easily bring one game to a wide variety of machines. By writing just one interpreter for any given machine, he immediately opened it up to his entire catalog. In the chaotic marketplace of the late seventies and early eighties, in which new machines came and went with the seasons and there might at any time be as many as two dozen viable but mutually incompatible machines available at any given time, this was huge. It was a model that worked particularly well for IF because of its reliance on plain text. The machines of the time were distinguished from one another primarily by their multimedia capabilities. Users of more capable machines tended to be very critical of products that did not make good use their machines’ power, but targeting such machines from the beginning would likely yield a product that would have to be substantially downgraded to run on less impressive hardware. Thus it was a delicate balancing act for developers hoping to reach more than a sliver of the market, but one which developers of IF could largely disregard. All machines on the market by 1978 could after all display plain text with reasonable facility.

Adventureland sold very well, and marked the beginning of Adventure International, the company founded by Adams and his wife Alexis. Soon the Adams’ were porting their game to the other popular microcomputers of the day, and within six months a second title, Pirate Adventure, had appeared. For a number of years, Adventure International thrived, eventually releasing almost twenty games. The technology behind them did improve somewhat, and in his later game Adams even began to include hand-drawn color graphics to illustrate the scenes, but only toward the end of Adventure International’s run did he devote serious attention to improving the parser. Thematically, Adams never really progressed beyond simplistic treasure hunts. Most of his titles took the gameplay of his first two games and merely transported it to a different setting. Adventure International’s early games succeeded because they were the only games in town. Nothing else would run on those primitive early machines. When technology advanced, however, and Adams’ games failed to advance with it, their days were numbered. Adventure International peaked in late 1983 at some fifty employees. Less than two years later, it went bankrupt and disappeared.

One of Adventure International’s final games, based on

the Marvel Comics Spider Man character. Note that, in spite

of the potential of the Marvel license, the game looks remarkably

similar to Adventureland, released six years earlier.

Today, there is a certain nostalgia for Adams’ games, largely because they were the introduction to adventure gaming for that first generation of home computer users. Their merits do not extend much beyond being first, however. They are balky and frustrating, and the stories they tell are so sparse that even calling them IF strikes me as something of a stretch. Their greatest virtue in Adventure International’s early years was the fact that they were able to run on extremely primitive hardware, targeting machines with just 16K of RAM and a tape drive for storage. When more powerful machines began to appear for reasonable prices, Adams failed to expand his vision accordingly. In an article in the March, 1981, issue of Softside magazine, Adams speaks about his game design process, stating that the average game takes him about one month to complete, start to finish. In the next chapter I will discuss the time-consuming authoring and exhaustive testing process at Infocom, the company that represented the gold standard of IF. At that point, we will get a more complete picture of just how primitive Adams’ games were compared to the best IF available even then. While one might mourn the early passing of Adams’ pioneering company, it is hard to argue that it did not deserve its fate.

Sierra On-Line

A number of other companies began releasing IF games in the wake of Adventure International’s initial success, inspired equally by Adams’ games and by the mainframe Adventure. Most notable among these was On-Line Systems, whose founders Ken and Roberta Williams beat Adams to the punch in being the first to include illustrations with their games. Ken was working on IBM mainframes as a business programmer in 1979 when he showed Adventure to Roberta. After playing it and some of the early IF games available on the family’s Apple II, Roberta decided to try her hand at designing her own game. She sketched out on paper the rudiments of an Agatha Christie-style locked-door mystery and showed it her husband in the hope that he would agree to program it for her. Ken was impressed, but felt that “’To really sell, you need more. An angle. Something different’” (Levy 297). Primitive black and white illustrations, little more than stick figures really, were that “angle,” and luckily so, for the game little else going for it even by the standards of the time.

Due to the novelty of its graphics, Mystery House did very well for the Williams, and provided the capital to get Online Systems, soon to be renamed Sierra Online, properly off the ground. The company released several more of their so-called “Hi-Res Adventures” over the next few years, along with various other non-IF games, such as clones of popular arcade hits. None of their works of IF were particularly distinguished, although two, Softporn Adventure and Time Zone, are worthy of brief mention for other reasons.

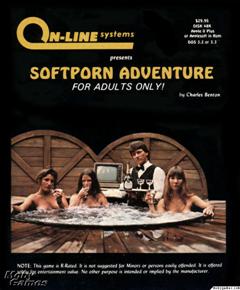

Softporn Adventure was perhaps the first adult-oriented piece of IF. In this predecessor to Sierra’s much better known Leisure Suit Larry series of graphical adventures, the player is tasked with relieving the game’s protagonist of his virginity. Ken Williams, always looking for that mythical “angle,” made the most of the game’s raciness, even plastering a picture of his wife and two company employees topless in a Jacuzzi on the game’s box.

Softporn’s cover art, featuring Roberta Williams at far right (1981)

Softporn was poorly written and poorly designed, and not even particularly titillating. (It is actually the only all-text adventure ever released by Sierra, which is ironic considering its theme.) As the first risqué piece of IF, though, it was important in its way, being as it is the first in a long line of adult games stretching right to the present day. It set a precedent in another way, too, for most of the games produced by the modern Adult Interactive Fiction (AIF) community are just as bad as Softporn.

One of the final entries in the Hi-Res Adventures line, Time Zone, was notable for its sheer size. This time-travel adventure spanned a staggering twelve Apple II disk sides and advertised 1500 rooms to explore in 39 separate time periods. However, its price of $99 was equally excessive, the exasperating two-word parser of Mystery House remained virtually unaltered, and the game’s only real advance over its predecessors was in its bulk.

Shortly after Time Zone’s release, Sierra published another of Roberta’s games, King’s Quest, in which the player could for the first time manipulate a graphical representation of her on-screen alter ego directly using the arrow keys or a joystick.

King’s Quest (1983)

While King’s Quest and its successors over the next several years would continue to bear the vestiges of IF in the form of a simple parser, they really mark the beginning of the graphical adventure, a form that, while interesting and worthwhile in its own right, has evolved into something very different from IF. It was in this area, not IF, that Sierra would make its reputation with a long string of games stretching to 1999. Judging by the less than breathtaking literary quality of the company’s early text-based work, perhaps it was just as well. It seems their hearts were never really in text adventuring, and once the opportunity arose they moved away from the form as quickly as possible. Ken Williams’ “angle” of graphics became the company’s guiding principal. Sierra still exists as a publishing house today, although it has moved even farther from its roots and no longer publishes adventure games of any sort. Ken and Roberta, and virtually everyone associated with the company’s graphical adventure glory days, left long ago.

Even as Adventure International, Sierra, and various other companies were cranking out their simplistic two-word parser adventures, another company was lapping the field with a game of stunning sophistication. To understand the origins of Infocom and that first remarkable game of theirs, Zork, we must return briefly to the world of mainframe computing.

Sources for Further Investigation

Games:

Adventure. 1976. Will Crowther and Don Woods.

An MS-DOS executable created from the original Fortran source is available at http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/games/pc/adv350de.zip.

A more modern, user-friendly re-implementation by Graham Nelson is http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/games/zcode/Advent.z5.

Adventureland. 1978. Scott Adams; Adventure International.

Released as shareware by Scott Adams.

http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/scott-adams/games/scottfree/AdamsGames.zip.

King’s Quest. 1983. Roberta Williams; Sierra On-Line.

Mystery House. 1980. Ken and Roberta Williams; On-Line Systems.

A faithful re-implementation of the original is available at http://turbulence.org/Works/mystery/games.php.

Pirate Adventure. 1978. Scott Adams; Adventure International..

Released as shareware by Scott Adams.

http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/scott-adams/games/scottfree/AdamsGames.zip.

Questprobe #2: Spiderman. 1984. Scott Adams; Adventure International.

Released as shareware by Scott Adams.

http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/scott-adams/games/scottfree/AdamsGames.zip.

Softporn Adventure. 1981. Chuck Benton; On-Line Systems.

Time Zone. 1982. Roberta Williams; On-Line Systems.

Other Works:

Adams, Scott. “Say Yoho.” Softside, March 1981. Available online at http://www.if-legends.org/~aimemorial/sayyoho198103.html.

Jerz, Dennis G. “Scott Adams Speaks.” http://jerz.setonhill.edu/if/adams/scottspeaks.html.

Kidd, Graeme. “Great Scott!” Crash #15, April 1985. Available online at http://www.crashonline.org.uk/15/adams.htm.

Levy, Steven. Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Penguin: New York, 1994.

Liddil, Bob. Review of Zork. Byte, February 1981.

Nelson, Graham. The Inform Designer’s Manual. 4th ed. The Interactive Fiction Libray: St. Charles, Illinois. 2001.

Available online at http://ifarchive.flavorplex.com/if-archive/infocom/compilers/inform6/manuals/designers_manual_4.pdf.

Veit, Stan. “MITS Altair 8800.” http://www.pc-history.org/altair.htm.